- Home

- Timothy Ireland

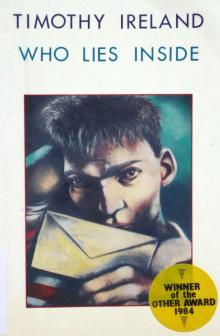

Who Lies Inside

Who Lies Inside Read online

TIMOTHY

IRELAND

WHO LIES INSIDE

It was as it out of the corner of my eye I could see a stranger standing in the shadows and I was scared to look too closely in case I saw who it was. Worst of all the stranger seemed to have wriggled under my skin, or had grown inside me all my eighteen years, only now for some reason that stranger was not content to stay in the shadows but wanted to step out into the light and be seen.

“Timothy Ireland is close enough to adolescence to know its unique problems, yet his insights are formidably adult” (Company).

Timothy Ireland,

photo by Joanna Allum

Timothy Ireland was born in Southborough, Kent in 1959 and now lives and works in London. His previous publications include the novels Catherine Loves and To Be Looked For.

First published in May 1984 by Gay Men’s Press

(GMP Publishers Ltd), P O Box 247, London N15 6RW

World copyright © 1984 Timothy Ireland

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Ireland, Timothy

Who lies inside.

I. Title

823’.914[F] PR6059-R4/

ISBN 0-907040-30-6

Cover art by Graham Ward

Photoset by Shanta Thawani, 25 Natal Road, London N11

Printed and bound by Billing & Sons Ltd, Worcester

Table of Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

to

MILES PARKER

and

Jack, for his kindness

David Fleckney, despite silence

and Rosalyn Connor and her Green Bed.

This is also for Mum and Dad,

my family and friends.

1

I suppose, first of all, I should tell you my name. It’s Martin Conway. From the outside I look just like an ordinary young man, though perhaps I’m a bit taller than most. My friends in the rugby team at school call me Jumbo. It’s my nickname. I don’t mind it, not really … You might see someone like me on any street in any town, walking along not too sure of myself, a tall, well-built young man in jumper and jeans. But inside something’s different.

I’m not sure when I actually realised it. Perhaps it was that overcast afternoon of the last rugby match of the season. We were playing Shipham and winning by two clear tries. Dad was on the sidelines ecstatic, shouting wild encouragement, cheering us all on. Mum stood quietly beside him, not waving her arms or anything, just enjoying watching me play.

It was always like that every Saturday afternoon of the season. Always. Then something inside me changed, or perhaps it had been there all along, from the very day I’d been born, only I hadn’t noticed it before, not properly anyway.

One thing for sure, nothing would ever be the same again.

I found out afterwards that his name was Gerald. He wore the green and white hooped colours of the Shipham side. We’d played Shipham once before this season, beating them away from home. Gerald hadn’t been playing that day. He was new to their side, and smaller, of a slighter frame than the normal rugby player, but, as the team soon found out, he was fast, able to leave everyone clear behind him if he was allowed to break out.

Besides being the smallest on the field, he was also the best looking. Thick black hair cut short, wide blue eyes and a nose as small as a girl’s. He was broad-shouldered, but slim and nimble-footed.

“We’re going to have to nobble that pretty boy,” Steve, my best friend, told me after Gerald had swept Shipham into the lead with a well-run try that had showed up the shakiness of our team’s defence, namely myself. I’d never liked playing back, but Tom, our trainer, had told me that I was too heavy and slow to play on the wing.

“You’re going to have to scare him, Jumbo,” our captain said. “Make it look as if you’ll break his bloody neck.”

“Don’t treat him like china, Jumbo. Hurt him.”

The next time Gerald broke free I could sense the rest of my team turning to watch me do my best at pretending to be a wild animal. I brought him to the ground more heavily than usual, fearing for my pride and my team’s record — we hadn’t lost once at home this season — and let my full weight crash down on his slight frame. I could hear the breath hiss out of his lungs and I moved to get up, planning to rest my boot on his chest as I did so, not kicking him but applying a little warning pressure.

I glanced down at his face. I could see fright tugging at his mouth, and then I noticed the light in his eyes. There was fear there too, but also something else dark in his blue eyes.

Excitement.

He saw me hesitate, my boot poised above his chest, and then he caught my glance, realised I knew, and smiled quickly, curling his bottom lip, as if a secret had passed between us, something slyly slipped from hand to hand.

I wasn’t exactly sure what I knew then, but I was scared. It was silly really, since I’d meant to put the frighteners on him. For the rest of the match I couldn’t keep my eyes off Gerald, which was just as well as he had two more good chances for tries only I brought him smack down into the muddy pitch each time.

“I think you’ve got it in for me,” he said, in a quiet voice, and I reached out one hand and helped him up off the ground, seeing again the funny light in his eyes and looking away because it worried me.

Then our forwards went to work and scored two tries and the whole of our team pulled together, Dad and Tom cheered from the sidelines and Shipham no longer stood a chance, even with Gerald on their side.

In the second half it was colder and the game grew scrappy. We scored another try and then Shipham seemed to give up and surrender. I tried to catch Gerald’s eye once or twice, but he was always far away after that, on the other side of the pitch, yet I had the strange feeling that he knew I was watching him. He kept walking so carefully as if he was on a catwalk like a beauty queen or on stage like an actor taking neat steps across the set. Once when he was ten yards away he turned and looked at me, only this time there was no funny smile on his face because he was staring straight into my eyes.

The blood ran to my face and I felt silly as if some girl had seen me with my flies undone or I’d accidentally trodden on some squashy dog turd. Only it was worse than either of these things because I wasn’t unzipped or mucky-footed. I had no reason to be embarrassed, and yet I was. I wiped the sweat off my face with a dirty hand and saw that Gerald was turning away and walking up field. I wanted to follow him, to run up and say “Hi”, and see what he said then. I wanted to understand that look in his eyes. I even wanted to touch him, just lightly on the face, to make sure he was real. I’d never felt any of these things before. I think that’s why I was so scared. I wasn’t me any more. I was someone else, and I didn’t like that feeling.

I turned then and looked across at Mum standing on the sidelines. She gave me a limp smile, holding her warmth in the way she always did, as though if she let herself go, all the good feelings inside her would run away and leave her with nothing else to give. I smiled back at her, not daring to wave for fear of what the lads would think, and saw her glance up at the grey sky as if she was worried it might rain. Dad, who was counting down the minutes to our victory, checked his watch and called out “Time” to Tom, who was refereeing.

Thankfully Tom nodded his head at my father and took no notice. I sometimes wondered how Mum could stand patiently beside my loud-mouthed father and not run away and bury her head in the ground. The rest of the team liked my Dad. They thought he was a good sport to come along and shout at them whatever the weather. Rain or shine, Dad would always be there, and some

times he’d drag Mum along too if we were in a cup tie or when it was an occasion like today with the last match of the season.

At one time Dad had felt lost when Easter came and there were no more matches to see on Saturday afternoon, but then he got friendly with Tom, our sports teacher and trainer, and followed him along to athletics fixtures in the summer. Dad would spend evenings reading books on running, hurdling and throwing the javelin, and later, standing beside the quiet-voiced Tom, he would throw in what he called a little helpful advice to particular struggling schoolboys he took a fancy to. Sometimes he used to ask me to come along with him, but I always felt guilty that it wasn’t me out there sprinting or jumping for the school, earning colours that could be stitched like medals onto my blazer. But the rugby colours were enough, I thought, and anyway I was too heavy to be a fast runner, too reluctant to put the shot.

Dad always found someone to follow, someone he could pass on his advice to. I used to think he should have had more children, more sons, instead of just me. Sometimes I wondered what he’d have been like if he’d had a daughter. And what I’d have been like with a sister. I’d never really had a girl to talk to, no one I could be feeling with. It was always the lads in the rugby team and the talk in the showers and the backs of classrooms that should have turned the air blue.

I wondered what Mum would have been like with a daughter or even another son, more children to bring the life out of her, make her smile and tease the way she used to when I was younger. Dad and Mum always seemed afraid to smile at each other, perhaps Mum didn’t think it was right to with grown men, and as I’d grown up she’d become like that with me.

Tom blew the final whistle and the match was over. We thumped each other on the backs and half-heartedly cheered the other team. Everyone was covered with dirt and hot and tired. We congratulated one another over and over again, unsure of what else to say. Inside, I think we were all a little sad. Most of the team, like myself, were in the Upper Sixth, and would be leaving school forever in a few months. We’d never play together as a team again. Before we left the pitch we picked up the grey-haired Tom and hoisted him onto our shoulders, carrying him like some trophy we’d won. He tried to pretend he wasn’t pleased or sad, but when I looked hard at him I could see he’d gone all misty-eyed. He kept telling us we were great lads, the best, and he was proud of us all. Not one home match lost all season. It was a school record, he thought. We were great lads. He’d always known we could do it.

Everyone kept shouting, even when we went into the changing-room and threw our captain, Steve, under the cold showers. It was as if we were all afraid to be quiet, worried about thinking how this was our last match together. Dad stood there amongst us all, patting us on our backs and grinning broadly. He brought out cans of beer to celebrate. A surprise, he said, though I’d seen it coming all along. Everyone pulled open cans of beer and drank his health and called him Spectator of the Year, so it all went, I thought, just as he’d planned. I wondered about Mum then, on her way home, putting up her umbrella against the rain that had started to fall, entering her council house alone. She’d put the kettle on, I thought, sit down and drink her cuppa and then set about preparing Saturday tea.

I half wished she’d been there to share in the celebrations, but then I realised all the noise and shouting would have embarrassed her. And then thinking that, I wondered what all the fuss was about. Whether we had really achieved anything? I saw myself standing there on the edge of the crowd with a can of beer in my hand and nothing to say. I felt sweaty and filthy and wanted to soak myself under the hot shower, but it seemed a shame to break up the party.

I’d forgotten all about the Shipham team who’d showered and changed already and were waiting for the coach to arrive and take them home. Forgotten all about Gerald. Someone nudged my arm and I turned.

He looked even less like a rugby player off the field, short, slim, good-looking with his dark hair and neatly arranged features. He glanced at me almost shyly, then met my eyes and smiled as if he was pleased and uncertain at the same time. Then he handed me a piece of paper and I took it and shoved it in a pocket of my jeans which were hanging from a peg next to me.

I wanted him to say something, to explain his funny smile to me, explain why he bothered me so much, but he shrugged as if he thought I already understood.

“Perhaps you’ll call then,” he said, softly.

I nodded automatically, not thinking about what I was doing, and then one of his team mates called out to him. He turned back to me quickly and this time his funny smile had been wiped away. I could see the anxiety in his eyes, could tell that he was scared, as if he was suddenly aware of my ignorance, afraid I would misunderstand.

“See you,” he said, but I could read the tremor behind the nonchalance, and then he walked away, out of the changing-rooms with his friends and onto the coach. As he went away I realised that his sports teacher was staring at me. It was like I’d done something wrong, only there didn’t seem any harm in a useless piece of paper.

The Shipham sports teacher said goodbye to Tom and wished us all the best and then he left us for the coach. For some reason I felt relieved when I heard the rumble of the coach pulling away. It was as if I was free, off the hook. I turned round, taking a swig of the canned beer, and joined in with the rest of the team in a rowdy chorus of “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow”.

We picked Tom up and paraded him round the changing-room, nearly knocking his head off on the low ceiling. Then, in case he misinterpreted our actions as affectionate, we threatened to throw him in the cold showers, clothes and all. Tom protested that he was an old man with a weak heart, but we knew he was only forty-one and threw him in, rewarded by the stream of abuse he spluttered at us all.

We stripped off our kit, peeling off shorts, shirts, jockstraps and socks, and leaving them in untidy heaps we raced for the faucets that for some reason gave out the hottest water. As I soaped myself I looked out through the steam and saw Dad watching us forlornly like a child that had been left behind. I was sorry because I knew that more than anything else he wanted to be naked, splashing and laughing with the rest of us.

He caught my gaze and flinched, shying away from the sympathy in my eyes. Then he turned his back on me and walked away, knowing his part of the game was over.

I closed my eyes, putting my face right up close to the faucet as if the pressure of the hot water would wash all my troubled thoughts away.

“You going out, Martin?” Mum asked.

I was sitting there in the armchair watching some film on television where everyone chased everyone else through the jungle while spiders and snakes regularly fell from trees onto the heroine who screamed convincingly while music from the man-eating savages beat menacingly in the background so that the rugged hero could remain undaunted. I was quite enjoying it really. A good yarn as Dad would say, and I didn’t feel like moving.

“Of course he’s going out,” Dad said loudly, shutting my mother up. “He’ll be out drinking with the lads. Celebrating.”

I was meant to meet Steve and Jim in the Roebuck at eight o’clock, only for some reason I didn’t want to go. I felt safe at home watching the TV. I knew Dad would go out and have his Saturday night bevy later on and then there would be peace. Perhaps I could even say something to Mum, get her to smile while she did the ironing. It niggled me that Dad left her at home on her own while he boozed with his lads and told tall stories about the gifted soccer players of years ago.

“You don’t want to be late,” Mum said quietly, “if you’re meeting someone.”

“I won’t be late,” I protested.

“Go on, lad, shift it. You’re wasting valuable drinking time.”

“All right, Dad,” I said sharply.

I gave him a quick glance.

He was still handsome in a faded sort of way, but I wondered sometimes why Mum had chosen him all those years ago.

Dad looked at me as if he could read my thoughts and didn’t much car

e for them. Then he stared at his feet as if someone had unfairly clipped him around the ear. Dad regularly stared like that at his feet and it always worked whether it was Mum or me, only today it annoyed me that I felt sorry. I wondered if he’d perfected this trick as a little boy. I said nothing and turned away, only Mum saw the anger bright in my eyes.

In the hallway, Mum pressed three pound notes into my hand and I couldn’t help feeling guilty for taking them.

“There you are,” she said quietly, and I wanted to pick her up because she was so small and worn out, looking ten years older than she should have done. Instead I put the money into my back pocket and mumbled thanks.

“Your Dad was pleased with you,” she whispered, afraid he would hear.

I was silent, not wanting to believe her, even if it was true. Then I saw the anxiety cloud her eyes and was sorry because I didn’t know what to say. It was always like this with Mum. Wanting to give, but forever feeling empty-handed.

“You played a good match,” she said again. “I was proud.”

That shocked me. I stood there as if my insides had turned into stone. I knew the effort those last three words had cost her, but couldn’t think of any way of paying her back. Mum hated it when I kissed her, unless it was Christmas or my birthday and even then she seemed to cringe. Once when I was a kid she’d nearly died when I ran up and threw my arms around her in front of Dad. Afterwards, in the kitchen, I heard him ask her if I always behaved like that. He was worried, he said. He didn’t want his only son turning into a mamma’s boy. Mum never made a noise. Dad’s word was law. Ever since I could remember they’d never argued. Dad said his bit and that was that. I used to hate her for not standing up to him, especially when what Dad shouted at her about was me.

Who Lies Inside

Who Lies Inside